The story of the 31st Maine Volunteer Infantry falls outside the scope of Maine Roads to Gettysburg, since the regiment wasn’t mustered in until April 1864, months after the July 1863 battle in Pennsylvania. Still I have a personal interest in the regiment ever since discovering that my great-grandfather, Daniel True Huntington, served with it as a private in Co. I and was injured in the fighting outside Petersburg. While looking through the regiment’s files in the Civil War Regimental Correspondence at the state archives in Augusta, I found some interesting letters, which I will share here.

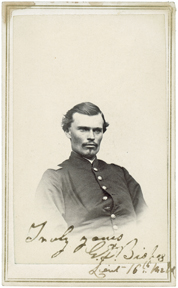

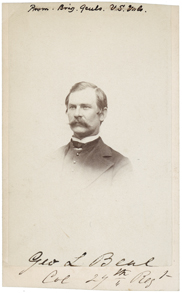

Col. Daniel White, who commanded the 31st Maine (Maine State Archives).

Colonel Daniel White of Winterport, Maine, started his Civil War with the 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry. After that regiment ended its service, White joined the newly formed 31st Maine as the captain of Co. A. When the 31st Maine left Augusta in April 1864, it was under the command of Lt. Col. Thomas Hight of Augusta and the 31st Maine was assigned to the IX Corps division of Robert Potter. It suffered terribly during the hard fighting in the Wilderness and Spotsylvania and on the road to Cold Harbor. Hight was later promoted to full colonel, but resigned in May due to ill health. His second in command had also fallen ill so White, by then a major, received command of the regiment and a promotion to colonel.

White did not remain in command for long, although he did lead the regiment on the march from Cold Harbor that started in the early hours of June 12, and then across the pontoon bridge over the James River, and on to the outskirts of Petersburg. In the predawn hours on June 17, the regiment attacked the Confederate lines, an action described in the 1865 book Maine in the War of the Rebellion:

It was fifteen minutes past three. The brigade commanders had timed their watches, that the movement might be in concert. There was silence along the line. The first faint rays of coming daylight began to appear. The time had come. The word of preparation was whispered along the lines. The men, cramped by lying in the trenches, rose to their feet, and dressed their ranks in silence. They grasped their muskets with a nervous energy. There was no clicking of gunlocks. Their spirits roused to the tremendous moment. Now! It was not shouted but spoken lightly. Yet it is powerful enough to put those lines in motion. They go up the bank holding their breath, running, leaping, rushing. There are four flashes of light, a line of fire, one volley only! They are up to the breastworks. On them! Over them! Surrender! The movement is a complete success. Six pieces of artillery and six hundred prisoners is the result, the glorious work of three minutes.

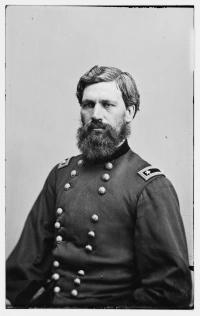

On July 30, the 31st Maine was one of the leading regiments to storm the enemy lines following the explosion of a mine that Pennsylvania coal miners had constructed beneath the Confederate entrenchments. In the ensuing Battle of the Crater, the regiment was “reported to be captured almost entire,” noted division commander Potter. White was among those taken prisoner. (It appears that my ancestor was injured in this fight, when he was storming the enemy’s works and fell into the ditch surrounding them, suffering injuries that might have included broken ribs.)

On May 2, 1865, Colonel White wrote to the state’s adjutant general, John Hodsdon to ask a favor. White was on his way with other exchanged Union prisoners to Annapolis, Maryland, to wait for his discharge from the army. “General, I see by the Papers that all Prisoners of War are to be Discharged,” he wrote to Hodsdon. “Now Gen while I am willing to leave the Service at any time that my Regt is mustered out, I am very anxious to remain and join the Regt so as to come home with it, having been identified with the same since its organization and commanded the same up to my Capture and God and those who have been Prisoners only know much we suffered while there.

“And I think it would be very unjust after the service I have done in this war to send me home before the Regt. because I was so unfortunate as to be Captured while doing my duty in the field, and I think my record will show that myself and the 31st Me has never been found in the rear when there was fighting to be done. So that I think it nothing more than justice done that I be allowed to join my Regt. and come home with the same.”

Henry W. Palmer also served with the 31st Maine, but as a private. His parents were not happy when their son joined the army. On April 8, 1864, Henry’s father wrote to Adjutant General Hodsdon to express his misgivings. “The state of my wifes health has for a long time been precarious” said Palmer. “This morning I received a letter from Mr. Skinner and other near neighbors, stating that since my boy left, his mother has scarcely at or slept, and serious fears are entertained that she will relapse immediately into her former state of insanity unless he can be released. Can such a thing be [done] before he is mustered into service? If there is any way it can be done, for humanitys sake let me know. Write me at Quincy House Boston. It pains me thus to trouble you.”

The Palmers’ fears were realized when Henry was wounded on May 12 during the fighting in front of Spotsylvania and he had his right arm amputated at the shoulder. Despite the terrible wound, young Palmer wished to remain with the army, prompting another letter to Hodsdon from his father. “Henry would like to be retained in the Army, at least for a while, tho, with loss of his right arm he could do little in the field. This is also my wish in part, but more fully that he might on furlough go to his home in Cornith (where I am to be after this week) and as he already writes very well with his left hand, I wish him so instructed that he may be useful hereafter. In the mean time, any position he can fill, any duty he can perform in his countrys aid, will happily receive his energies, talent, time, wholly, or in part. To his father, Henry has been a good boy; to his country he has already been faithful, promt[?], uncomplaining, patriotic—and thus he will ever be.”

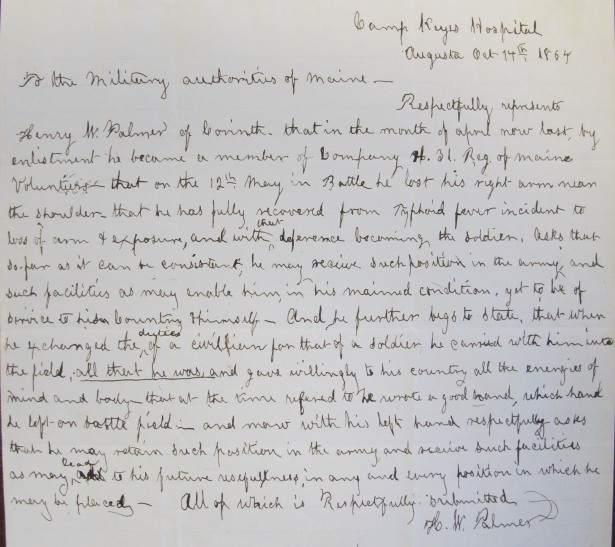

Henry himself wrote to “the military authorities of Maine” from the Camp Keyes hospital in Augusta on October 14. He had been learning to write with his left hand, and his writing was shaky. After explaining the loss of his limb, Palmer, referring to himself in the third person, said “that he has fully recovered from Typhoid fever incident to loss of arm & exposure, and with that deference becoming the soldier, asks that so far as it can be consistent, he may receive such position in the army and such facilities as may enable him, in his maimed condition, yet to be of service to his country & himself—And he further begs to state, that when he exchanged the duties of a civilian for that of a soldier he carried with him into the field, all that he was, and gave willingly to his country all the energies of mind and body—that at the time referred to he wrote a good hand, which hand he left on the battle field—and now with his left hand respectfully asks that he may retain such position in the army and received such facilities as may lead to his future usefullness, in any and every position in which he may be placed.”

I have not yet learned if White’s and Palmer’s requests were granted.

Maine Roads to Gettysburg is available for purchase now. You can find it on Amazon.com, BarnesandNoble.com, or at any fine bookseller near you (once bookstores reopen).

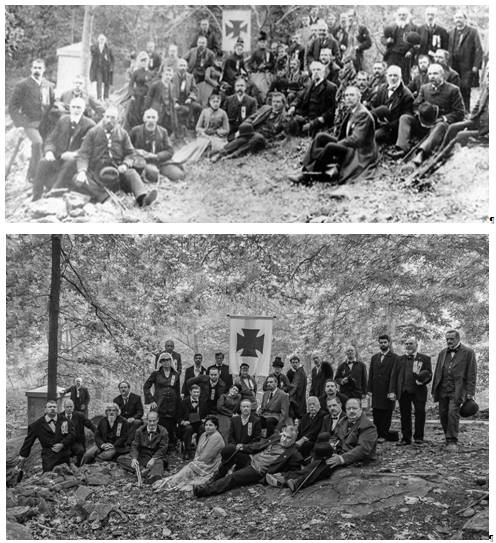

The original photo was taken on October 3, 1889. That was the day when Maine veterans from the state’s regiments that had fought at Gettysburg gathered on the battlefield to dedicate their monuments. The veterans of the 20th Maine—including Joshua Chamberlain, who had commanded the regiment on Little Round Top on July 2, 1863—and their family members met on the rocky spur where the regiment had fought more than a quarter-century earlier. “It is an occasion of great interest to us all, that after these twenty-six years so many of the survivors of the Twentieth Regiment, Maine Volunteer Infantry, are permitted to meet and stand on this historic ground, made sacred by the blood of our comrades who fell here in the defense of this vital position of the great battlefield of the war of the rebellion,” said Holman Melcher, president of the regimental association. Melcher, a farm boy from Topsham, had been a 21-yer-old teacher when he joined the 20th Maine in 1862. Melcher had led Color Co. F during the fighting and some credited him with starting the regiment’s final bayonet charge down the southern spur of Little Round Top, when he moved his company forward to provide cover for wounded who lay in front of him.

The original photo was taken on October 3, 1889. That was the day when Maine veterans from the state’s regiments that had fought at Gettysburg gathered on the battlefield to dedicate their monuments. The veterans of the 20th Maine—including Joshua Chamberlain, who had commanded the regiment on Little Round Top on July 2, 1863—and their family members met on the rocky spur where the regiment had fought more than a quarter-century earlier. “It is an occasion of great interest to us all, that after these twenty-six years so many of the survivors of the Twentieth Regiment, Maine Volunteer Infantry, are permitted to meet and stand on this historic ground, made sacred by the blood of our comrades who fell here in the defense of this vital position of the great battlefield of the war of the rebellion,” said Holman Melcher, president of the regimental association. Melcher, a farm boy from Topsham, had been a 21-yer-old teacher when he joined the 20th Maine in 1862. Melcher had led Color Co. F during the fighting and some credited him with starting the regiment’s final bayonet charge down the southern spur of Little Round Top, when he moved his company forward to provide cover for wounded who lay in front of him. The veterans had enjoyed a beautiful October day when they were here. We were not so fortunate 129 years later, as the morning was dank and misty. Fortunately, though, it was not actively raining as photo participants began trickling in before 8:00 that morning. Randy had obtained a permit from the National Park Service, and we had 45 minutes to finish our shoot. Photographer Tom Miller was behind the camera. Some of the participants, men and women, were wearing period clothing. Others, like me, were wearing anything they thought would look okay in the photograph. I had purchased my Italian-made wool sport coat that week at a Goodwill store for $7.95. I hoped it would pass muster. Someone had provided a collection of appropriate headgear, each one protected inside a plastic bag and ready to be distributed to the people who needed them. Randy had arranged for the production of reunion ribbons to match the ones that some of the veterans had been wearing. A banner with the V Corps’ Maltese Cross had been hung on a tree behind the spot where our group would assemble.

The veterans had enjoyed a beautiful October day when they were here. We were not so fortunate 129 years later, as the morning was dank and misty. Fortunately, though, it was not actively raining as photo participants began trickling in before 8:00 that morning. Randy had obtained a permit from the National Park Service, and we had 45 minutes to finish our shoot. Photographer Tom Miller was behind the camera. Some of the participants, men and women, were wearing period clothing. Others, like me, were wearing anything they thought would look okay in the photograph. I had purchased my Italian-made wool sport coat that week at a Goodwill store for $7.95. I hoped it would pass muster. Someone had provided a collection of appropriate headgear, each one protected inside a plastic bag and ready to be distributed to the people who needed them. Randy had arranged for the production of reunion ribbons to match the ones that some of the veterans had been wearing. A banner with the V Corps’ Maltese Cross had been hung on a tree behind the spot where our group would assemble.

Randy did an admirable job of getting us organized and in our places. Tom took a few pictures and, after examining them, Randy pronounced himself satisfied. Then our Chamberlain, Bob Mcfarlane, read an excerpt of a speech that Chamberlain made later during the reunion on October 3, 1889, words that are remembered and recited today.

Randy did an admirable job of getting us organized and in our places. Tom took a few pictures and, after examining them, Randy pronounced himself satisfied. Then our Chamberlain, Bob Mcfarlane, read an excerpt of a speech that Chamberlain made later during the reunion on October 3, 1889, words that are remembered and recited today. “In great deeds something abides,” he said. “On great fields something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls. And reverent men and women from afar, and generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream; and lo! the shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.”

“In great deeds something abides,” he said. “On great fields something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls. And reverent men and women from afar, and generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream; and lo! the shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.”

I certainly enjoyed talking at the visitor center at Gettysburg National Military Park for the official “book launch” in April, but talking about it in Maine was even better. At the Maine Historical Society talk, a friend of my parents’ surprised me by showing up for the talk. I used to go duck hunting with him. Someplace there’s a picture of him, my brother, and me in a hunting boat on the Sheepscot River near Wiscasset on a frigid morning during duck season. My dad probably took the picture around 8:00 in the morning, but we are all holding cans of Budweiser.

I certainly enjoyed talking at the visitor center at Gettysburg National Military Park for the official “book launch” in April, but talking about it in Maine was even better. At the Maine Historical Society talk, a friend of my parents’ surprised me by showing up for the talk. I used to go duck hunting with him. Someplace there’s a picture of him, my brother, and me in a hunting boat on the Sheepscot River near Wiscasset on a frigid morning during duck season. My dad probably took the picture around 8:00 in the morning, but we are all holding cans of Budweiser.