Maj. Gen. Joseph Mansfield was killed at Antietam on September 17, 1862 (National Archives).

The fighting started early on September 17, 1862, outside the little town of Sharpsburg, near the Potomac River and Antietam Creek. Joe Hooker’s I Corps had skirmished with the enemy the evening before, and “Fighting Joe” resumed the action when he started his troops south through a cornfield in the direction of a little white building known as the Dunker Church. Soldiers from Stonewall Jackson’s command, newly arrived from Harpers Ferry, were waiting. The bloody fight between Hooker’s and Jackson’s men ebbed and flowed over the cornfield throughout the morning.

Samuel Crawford’s brigade, including the 10th Maine, now belonged to the XII Corps, which had become part of the Army of the Potomac after Second Bull Run. The commander of the XII Corps was Joseph Mansfield, a Connecticut native, West Point graduate, and Mexican War veteran. Mansfield, a dignified 58-year-old with white hair and beard that gave him the appearance of an Old Testament prophet, had headed the Department of Washington but chafed to receive a field command. He finally got the assignment to the XII Corps on September 12, just in time to join his new command in Frederick.

Col. George L. Beal of the 10th Maine (Maine State Archives).

Colonel George L. Beal was leading the 10th Maine, although Crawford had placed him under arrest on September 2 after a dispute over some hay. Beal’s men, exhausted after a hard march through mud and rain, had taken the hay from a Rebel farm so they could make beds on the wet ground. When Crawford heard about it, he sent for Beal and told the colonel to order his men to return the hay under guard and then post sentries to prevent any more pilfering. Beal protested. His men were wet and tired, he said. He would tell them to return the hay, but would not insult them by forcing them to do it under guard, and he would not have any of his tired soldiers act as sentries that night. Crawford placed him under arrest, but restored him to command a few days later. Actions like that did not endear Crawford to the men of the 10th Maine. “If this were not a military mob we would turn out and give him a ducking in the river,” fumed John Mead Gould.

Such resentments were pushed aside now that the regiment faced combat. As Hooker’s corps attacked through the cornfield, Mansfield held his corps in reserve behind a forested area called the East Woods. It was a tense wait. Enemy shells soared over the soldiers’ heads and buried themselves in the earth behind. The roar of battle on the other side of the trees increased in volume, and more and more Union soldiers began pouring through the woods in retreat. “All of us did not notice these changes, and many did not even get up to look to the front, but we all saw Gen. Mansfield riding about the field in his new, untarnished uniform, with his long, silvery hair flowing out behind, and we loved him,” remembered Gould. “It never fell to our lot to have such a commander as he. Very few of us had ever seen him till three days before this, but he found a way to our hearts at once.”

Finally, it became time to advance. Beal ordered the regiment forward. Along the way, General Hooker rode up. “You must hold those woods!” he exclaimed. Bullets went snapping and whizzing past. Mansfield wanted his men to advance in two columns, feeling it was easier to handle them that way; Beal wanted to deploy his regiment in line of battle, and as soon as Mansfield had moved out of sight he did so, the general’s wishes notwithstanding. “And now came the moment of battle that tried us severely,” Gould wrote, “not that there was a sign of hesitancy, or show of poor behavior, but it is terrible to march slowly into danger, and see and feel that each second your chance for death is surer than it was the second before. The desire to break loose, to run, to fire, to do something, no matter what, rather than to walk, is almost irresistible. Men who pray, pray then; men who never pray nerve themselves as best they can, but it is said that those who have been praying men and are not, suffer an agony that neither of the other class can know.”

They reached a rail fence and fired at the Rebels. The Rebels fired back. One of them shot Beal’s horse in the head. As the colonel dismounted from the wounded animal, he was shot in the legs. His crazed mount then charged across the field and lashed out at Lt. Col. James Fillebrown, knocking him out of the battle with a fierce kick of its hind legs. Mansfield, in the confusion, became convinced that the 10th Maine was firing at Union troops. He rode over to stop them. A captain and a sergeant argued that they were shooting at the enemy. “Yes, Yes, you are right,” Mansfield conceded, and then Rebel bullets struck him. Gould was standing nearby. At first he thought the bullets had hit only Mansfield’s horse, but as the general dismounted, the wind blew his coat open and Gould saw blood streaming down his side. Gould and two other soldiers from the regiment helped the mortally wounded general to the rear, where he soon died.

After the war Gould became somewhat obsessed with marking exactly where Mansfield had been wounded, and in 1895 he published Joseph K.F. Mansfield, Brigadier General of the U.S. Army: A Narrative of Events Connected with his Mortal Wounding at Antietam, Sharpsburg, Maryland, September 17, 1862. “It was bad enough and sad enough that Gen. Mansfield should be mortally wounded once, but to be wounded six, seven or eight times in as many localities is too much of a story to let stand unchallenged,” Gould wrote.

Adapted from Maine Roads to Gettysburg, which is available for purchase now. You can find it on Amazon.com, BarnesandNoble.com, or at any fine bookseller near you.

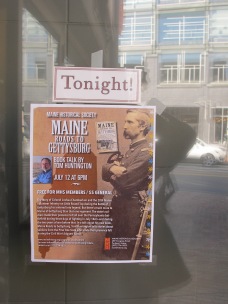

I certainly enjoyed talking at the visitor center at Gettysburg National Military Park for the official “book launch” in April, but talking about it in Maine was even better. At the Maine Historical Society talk, a friend of my parents’ surprised me by showing up for the talk. I used to go duck hunting with him. Someplace there’s a picture of him, my brother, and me in a hunting boat on the Sheepscot River near Wiscasset on a frigid morning during duck season. My dad probably took the picture around 8:00 in the morning, but we are all holding cans of Budweiser.

I certainly enjoyed talking at the visitor center at Gettysburg National Military Park for the official “book launch” in April, but talking about it in Maine was even better. At the Maine Historical Society talk, a friend of my parents’ surprised me by showing up for the talk. I used to go duck hunting with him. Someplace there’s a picture of him, my brother, and me in a hunting boat on the Sheepscot River near Wiscasset on a frigid morning during duck season. My dad probably took the picture around 8:00 in the morning, but we are all holding cans of Budweiser.